If you can distill fashion to a handful of designers who shifted culture so seismically they created their own epochs – and you can – Vivienne Westwood would be there waving her orb in a Harris Tweed crown. At 430 Kings Road, a shop (and collection) known as Worlds End since 1980, and before that, Let it Rock, Sex, Seditionaries, with Malcolm McLaren (a true abrasive, intellectual, perceptive genius), she really shook the cage.

First came the electric shock of Punk – “You’re gonna wake up one morning and know what side of the bed you’ve been lying on!” – tying up disaffected youth in bondage wear and printing muslin tops and ripped t-shirts with tits, naked cowboys, swastikas, the Cambridge Rapist and anything indecent enough to risk arrest if you passed a bobby on the beat. Then something altogether more grand: bending time and rewriting history, pillaging the V&A for technique and clashing references to create something new, something heroic and romantic, like explorers of wild frontiers.

Alien and odd, these clothes, much as they snatched time, like the thirteen hour clock on the front of Worlds End going backwards, are timeless. They are their own vocabulary. Visit the wonky-floored Chelsea galleon and you can still buy the asymmetric drunken shirts which drag your body to one side, Pirate boots and Buffalo hats, a mecca of the unique. Whilst the cuts remain the same, Westwood, on her current environmental crusade, uses surplus fabric from her Gold Label collections to create small-batch exclusives for this shop only.

The philosophy of Worlds End has always been DIY, as much as it has been unisex. Even today, a time when you get nothing for nothing, if you go on the blog there is a pattern to make your own drape shirt, from whatever you find lying around. Get a life!

Murray Blewett has been working with Westwood for neigh-on 30 years. And before that he was in the shop all the time, buying the clothes – which are so culturally significant, they’ve found their way into museum collections around the world, like the V&A, appropriately enough. Today Blewett works on both Red Label and Worlds End, maintaining a personal dialogue with King’s Rd. It is Blewett who is in charge of the Westwood archive, no one else is allowed to touch it.

Whilst the area of Worlds End itself is changing, the shop still stands proud. Brilliantly, the Chelsea Conservative Club, next door, has vacated. How’s that for an image? As the infamous mock Tatler cover goes, ‘This woman was once a punk’. And so it remains.

Dean Mayo Davies: What was your first encounter with Westwood?

Murray Blewett: Well, I’m not from London, I’m from the countryside, I’m an Essex boy. I’m a farmer’s son, so not from a fashion background at all. From the age of thirteen, fourteen I used to come to London on my own – this is mid-70s – [my parents] couldn’t really stop me. I absorbed all the music press like the NME and I found out about the shop [at 430 King’s Road], so I visited and I did buy a t-shirt. But I was very young, so can’t say that I was a great customer or anything.

DMD: Was it as terrifying as everyone made out?

MB: Yeah [laughing], I remember Jordan just trying to make you misbehave, offering you booze and stuff. I didn’t really start to be a proper customer until I went to fashion school and moved to London in 1980. In those days you used to get a grant and I spent most of my grant on Pirate clothes, and then had to live on nothing for the rest of the term. Too scared to tell my parents that I lived on baked beans and jacket potatoes and cigarettes. And I would start to really buy the things, it was all linked to going out. We went out a lot – everything was centred around Soho; Saint Martins was in Soho, which had a bar in those days, on Charing Cross Road. All my social life was really in one place then I found Kings Road, it was just great. Dressing up and going out, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday…

DMD: What’s great about Worlds End is that these clothes really became a portrait of culture, going out, as much as they were a gift to culture.

MB: Yeah, it was the beginning of so many things, but in a way it was the beginning of status through clothing, without being overtly flashy. If you think of status now you think of it just being bling, fur coat, logos. And you’re defined by your Louis Vuitton or whatever. But it’s really about not actually having any discerning taste, being very easy, just buying a handbag and that’s it. Object equals status. But the status you acquired from wearing Worlds End was sort of… some people didn’t know what to do with those clothes, they just didn’t have the right attitude, or they just had their Woolworths make-up and sort of… they’d get it really wrong and they were trying to make an effort. You couldn’t just go in the shop, buy a t-shirt and look cool. You had to really understand it, but it definitely gave you status, it meant that you were part of a little club, and you had entry to underground things. All the things which were really important at the time to you as a young person. So yeah, they had a hidden language.

DMD: There’s an innate quality that someone has to have to have to pull off these clothes. And then the inauguration of a tribe, it’s a really special thing.

MB: Vivienne always said all those clothes are to do with cuts and nobody had ever done anything like it before. Just putting neck holes to one side… people have tried but they’re Vivienne’s inventions, nobody will be able to do it as well as she has. And they do make you feel very different, you know. You’re conscious of your body in a different way. By putting a neck hole in a t-shirt off-centre it pulls all to one side, and then you’ve got all this weight on the other side. You have to embrace all this, or get used to it. And then when you do, and you aren’t scared of it you do feel a bit special. So this is what she means about empowering through clothing. When you get your head around it you do feel kind of super. The clothes always have an ethnic base, they are very artisan and handmade, using rectangles, making rectangles. She’s always been about saving fabrics and using things, DIY. Really different from everything else.

DMD: Where were you going out?

MB: Well, the first club that I went to was Steve Strange’s Club for Heroes at Barracuda. Then there’s Batcave and The Life. That’s when I was at college, that period from 1980, which is the real Worlds End core, ’81 to ’85. I started to work with Vivienne in ’86. But I wore those clothes all the way through and my favourite things where Hypnos, which is ’84, these sports things, funny all-in-ones. And that was really pushing the look… we used to wear them to Kinky Garlicky, Taboo and Heaven. People really dressed up to go to Heaven, believe it or not. Because we wouldn’t now [laughing].

DMD: I love that you got a job here because of your passion for the clothes.

MB: Yeah, all through college, as I told you, they always laughed at me because I had no money or anything, but I had all these amazing work for Vivienne Westwood, I’m so happy for you because you were always only interested in that.” I kind of didn’t realise, it was just normal to me. I met some friends, a generation older than I, who knew Vivienne and they’d worked with Malcolm and Vivienne back in the Punk days. Vivienne had been to Italy and was coming back, everything had finished with Malcolm and and I was introduced to her. It was the time of the Mini- Crini collection and I had a bit of money because I was working at the time on Kings Road and had a proper wage. So I was spending proper, good money! I was a customer and I just sort of fell into it, helping her out, she learned that I could make things, she said, “Oh maybe you could make some things, come in and help me.” I fell into it, just like you did in those days, “Come to the studio, see what you can do.” She just gave me tons to do, and that was it. And suddenly you’ve got a job six months later.

DMD: What was the first collection you worked on?

MB: The first collection I really worked on was Harris Tweed, so I made all the crowns.

DMD: Oh wow, that’s amazing.

MB: And I learned to make corsets. To begin with I was just really, really technical, just making things that I liked, I was good with my hands. I wasn’t designing, just making. It was a tiny company, I think there were six people in the whole company including Vivienne and myself. So if you think about what a global empire it is now…

DMD: And the impact Vivienne Westwood has had…

MB: It was tiny. Bella Freud was working here as well.

DMD: Yes! And she worked at Seditionaries…

MB: Yeah, Bella was super young because, with Seditionaries and Sex, Vivienne and Malcolm wanted all these really young girls. It was when Annabella Lwin from Bow Wow Wow was there. You just couldn’t do it now, there would be uproar.

DMD: How did Worlds End sit in the context of fashion at the time? It was the era of the power shoulder…

MB: Well that was it. And with the Mini-Crini Vivienne turned that upside down, she had little shoulders and this big crinoline skirt. It was this idea that she had from Jordan, whose looks were kind of ballet inspired, she wore leotards, and from the ballet Petrushka [in 1978] during the Punk time. She thought, ‘I’ll save that up for when I need something special, I’ll bring that out’. She was so sick of this one shape, flat shoes, big shoulders, space age, the future, all of that. Mini-Crini was really quite romantic. It’s funny considering her current stance on America, but it was actually a great looking Walt Disney interpretation. Think Mini-Crini, think of Minnie Mouse – puffed skirt, with the big spots. The pattern is actually three circles put together, and Mickey and Minnie are three circles, the face and the ears. Vivienne had always worked with rectangles, but now, for this collection she decided to make a softer silhouette with circles. It kind of informed the colours and the patterns, the sailor suits. It had this nostalgic, 30’s America and Lolitas feel. It was really powerful that look. For men she introduced really soft tailoring which had this kind of Savile Row feeling waistline, a bit Elvis, a bit 50’s. It doesn’t sound so radical now, but at the time it really was. I had a suit in very pale blue, she called it Elvis blue, one button, long-line, 50’s slightly zoot suity. It marked a moment where Vivienne really got her recognition. Paris started to really take her seriously and really rip it off. And that enabled the company to grow, as it has done ever since.

DMD: So can we talk about some of the collections, starting with the Pirate collection, and the dawn of the squiggle print?

MB: Well that pre-dates me because I was just a customer. But that was Vivienne’s first catwalk show, she was showing just in London, in Olympia. And she was very tired of this sort of negativity and the blackness of Punk. She felt that it wasn’t going anywhere and she wanted to totally turn it on its head. Everything was gold, gold, gold. Everything needed to be rich. You needed to stop living in the underground, and go overground, and dress up. It tied in with what was going on culturally, Malcolm informed her of the New Romantics. There was a very famous costume sale at Fox’s in Covent Garden at the time, all those kids, all of the ones who went on to fame, [Boy] George and Marilyn, [Princess] Julia, went to Fox’s closing down sale and bought all these costumes and really started dressing up. In amongst those would be pirate things, uniforms, Hollywood things. Malcolm wasn’t stupid, he knew what was going on, so he said “Vivienne you know, there’s something romantic in the air, what should we do? We need to look at history.” Vivienne went off and immersed herself in the V&A, and started to understand the cut of clothing from that historic perspective. The squiggle print came from something Jean-Charles de Castelbajac gave to Malcolm in Paris – ‘Oh take it, use it’. And that’s that. And some of the other patterns come from Apache, Native American imagery.

DMD: I love those prints in particular.

MB: So do I. And they informed the next collection, which are more or less the same things. Vivienne totally reinvented everything with Pirate, and that went on to inform the next few collections. There were these little touches of Apache print that were in Pirate, and that was a catalyst to make the make the next collection Savage, which was really about Native American culture.

DMD: What about Nostalgia of Mud?

MB: That was great, that was West End. It opened when I was at college, so ’82/83, it was only there a year because the neighbours really didn’t like that shop. The council complained all the time because it looked like an archaeological dig!

DMD: Fucking incredible.

MB: It was a really posh street, and they had a fibreglass map of the world put on the front of the shop. It was shit brown. But it wasn’t enough, so they tied brown tarpaulin over the top of it and then wrote Nostalgia of Mud. They did everything they could to disguise the frontage of this shop. As I say, it was supposed to look like an archaeological dig, so the inside was ripped out, it was just a pit. The ground floor was taken out and you went down into the basement and it was all scaffolding, it was really, really clever. You would walk down the scaffolding, there was a bubbling pit of mud in the middle of the floor, which kind of never worked [laughs]. It was just an incredible shop. That coincided with the launch of the [Nostalgia of Mud] collection, Buffalo girls and Malcolm with the whole music connection, it was really clever tying these things together. The love of mud, everything was brown and boiled, that’s where the famous Buffalo [Mountain] hat originated from. All different shades of mud.

It’s definitely good to listen to music of that time as well, Malcolm’s Duck Rock. It was the beginning of scratching and mixing, Malcolm was going to America all the time and bringing stuff back, and you’ll see some of the more sporty elements in there, even in that collection there’s things. In the Pirate collection there’s a historical square toe shoe, but it’s crossed with a Stan Smith upper. Taking something historical, 16th or 17th Century and mixing it all up. Vivienne collaborated with Keith Haring on Witches. She went to New York, met him and really liked him. She’s not a great lover of modern art as we know now, but she really said that Keith was an artist, he could draw anything, and if he’d lived longer he would have surprised us all. Because he invented a visual language.

DMD: In the way that she did with clothing. There was a fantastic Keith Haring exhibition in Paris last year…

MB: The French always loved him. It was a great thing, he literally just gave her an artwork and, you can’t imagine it now, in these days of corporate politics, said to her, “Use these however you want, because I trust you to do great things.” She did do the most brilliant things, and then we did start to sell in America, because there was that link, and with Madonna, who was very good friends with Keith. She’d always been a customer, and apparently she has a big collection, which I’ve only recently learned. There was always that link across the Atlantic, and that collection was so modern. It went from this ethnic thing to freeze frame and strobe lighting for Witches. I loved the thinking behind that one – it’s like when you capture breakdancing on celluloid, because they were moving so fast you’d get three repetitions in the image, it’s all about movement. So you had these big shoulders, three tongued shoes. Take a picture of strobing, you get this resonance.

DMD: It’s astounding. And Hypnos was Westwood’s first use of the phallus for buttons?

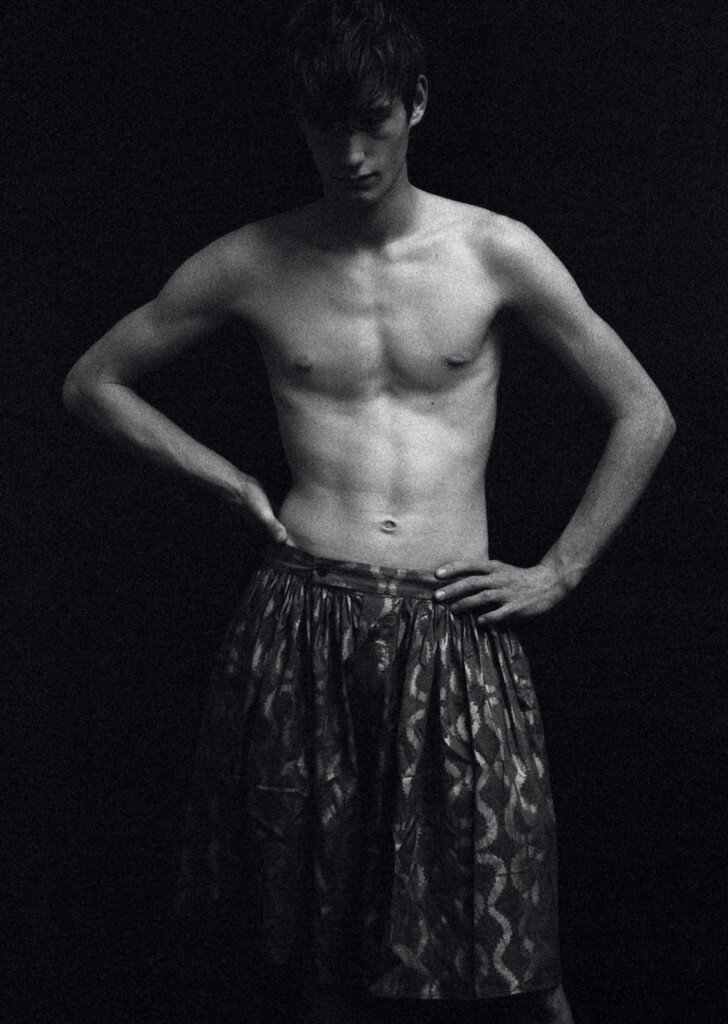

MB: I don’t know if Vivienne likes this but I love it, The Face called that collection ‘porno olympics’. Hypnos is the goddess of sleep, so it was a bit Pompeii, a kind of sexual activism, these working out clothes, they were called snake bodies. Vivienne used a minimal variety of fabrics, maybe four fabrics per collection. And it was all nylon. It made a big impact on London fashion at the time as it introduced fluorescent. So all of a sudden, even if you couldn’t afford to get Hypnos, because there were only limited amounts of these clothes made, it kind of altered the mass market in that everyone could wear fluorescent, and everyone could do their make up the same. Though it was this active look it wasn’t necessarily about being gym buff or anything, it had a gymnast feeling to it. The things were always really unisex, like I used to wear those Hypnos bodysuits and they were kind of androgynous, not really for boys, but you found a way of working it out. Well I did.

DMD: The Clint Eastwood collection has a such a powerful quote connected to it – “Sometimes you need to transport your idea to a world that doesn’t exist and then populate it with fantastic looking people.”

MB: Yeah, exactly. For Vivienne, Clint Eastwood summed up that picture of people in her mind. This great adventurer, this hero in this big space. What’s he going to do? What’s he going to find?

DMD: A lot of people who grew up wearing these clothes have gone on to become part of pop culture. Westwood created these heroic clothes and the people wearing them became posters on teenage bedroom walls.

MB: [Boy] George was one of the early ones. He worked in [clothes shop] The Foundry. There was a club around there called Planets and – everyone knows his story – he was a coat check boy there. A great club I used to go to was Le Beat Route and that’s where I first saw George wear all the Squiggle stuff. He went on to do fabulous things and he’s still a customer of Worlds End. Like I just told you about Madonna, who is someone you don’t really associate with it, but apparently she has this great collection because she realises how important the clothes are to our culture. Otherwise, I mean, we’ve still got loyal fans like Holly Johnson from Frankie Goes To Hollywood, who was in the shop on Saturday. Mad people like Pete Burns.

DMD: You still have this very direct dialogue with the shop, don’t you?

MB: Yeah, I try to go in there at weekends, I love that shop. I’d really be lost if that wasn’t there, because everything’s gone from the area. I think it’s incredible that people still visit, it’s still a mecca. People will travel down that horrible street of which there’s nothing on to differentiate it anymore, and where the people are so boring. Did you know Anita Pallenberg worked here for a while?

DMD: I’d no idea.

MB: Yeah, she was at Saint Martins and we got to know her and she’d always been a customer. She’s still going in there. And Michael Costiff pops in. Even Smile, the old hairdressers, that’s done. We’re the last one left, so we are busy fighting to keep it there.

DMD: 430 King’s Road has been through many names, yet Worlds End is the one that’s endured.

MB: And it’s called Worlds End because the area is called Worlds End. In the old days the 31 bus would start in Camden and go to Worlds End Chelsea, back and forth. It would say ‘Worlds End’ on the front, which is such a brilliant thing. Destination Worlds End! So it’s got that kind of Punk thing, like Malcolm had this bus which said ‘Nowhere’ on the front, when the Sex Pistols went on tour. It’s all a level, these totally British things. And that the area is called Worlds End just fits so perfectly with where Vivienne is right now, politically. It’s the world’s end if we don’t do something about it, it really is. These are the last days. And that clock spinning around, it all represents something, it reminds you.

DMD: What was intrepid is now also a bit poignant. [Westwood’s son from her first marriage] Ben Westwood is doing the Worlds End blog and he’s got a collection in the shop too.

MB: Yeah, he’s doing the blog. It’s really nice, Ben’s the same age as me and Vivienne really wanted him to come back to the business, because he’d been in and out a bit. Because he’s a photographer and was taking pictures at the time and had his own social scene with different people who worked here, we thought it would be really good to use it for his anecdotes, and to post his pictures and because of the family connection. To start to record that, because those things are so personal to him, using the blog as a platform to remember those stories. It’s a nice place for people to visit.

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD 430 KING’S ROAD ARCHIVE: THE WORLD’S END

MURRAY BLEWETT (WORLDS END, VIVIENNE WESTWOOD RED LABEL AND HEAD OF THE VIVIENNE WESTWOOD ARCHIVE)

INTERVIEW DEAN MAYO DAVIES

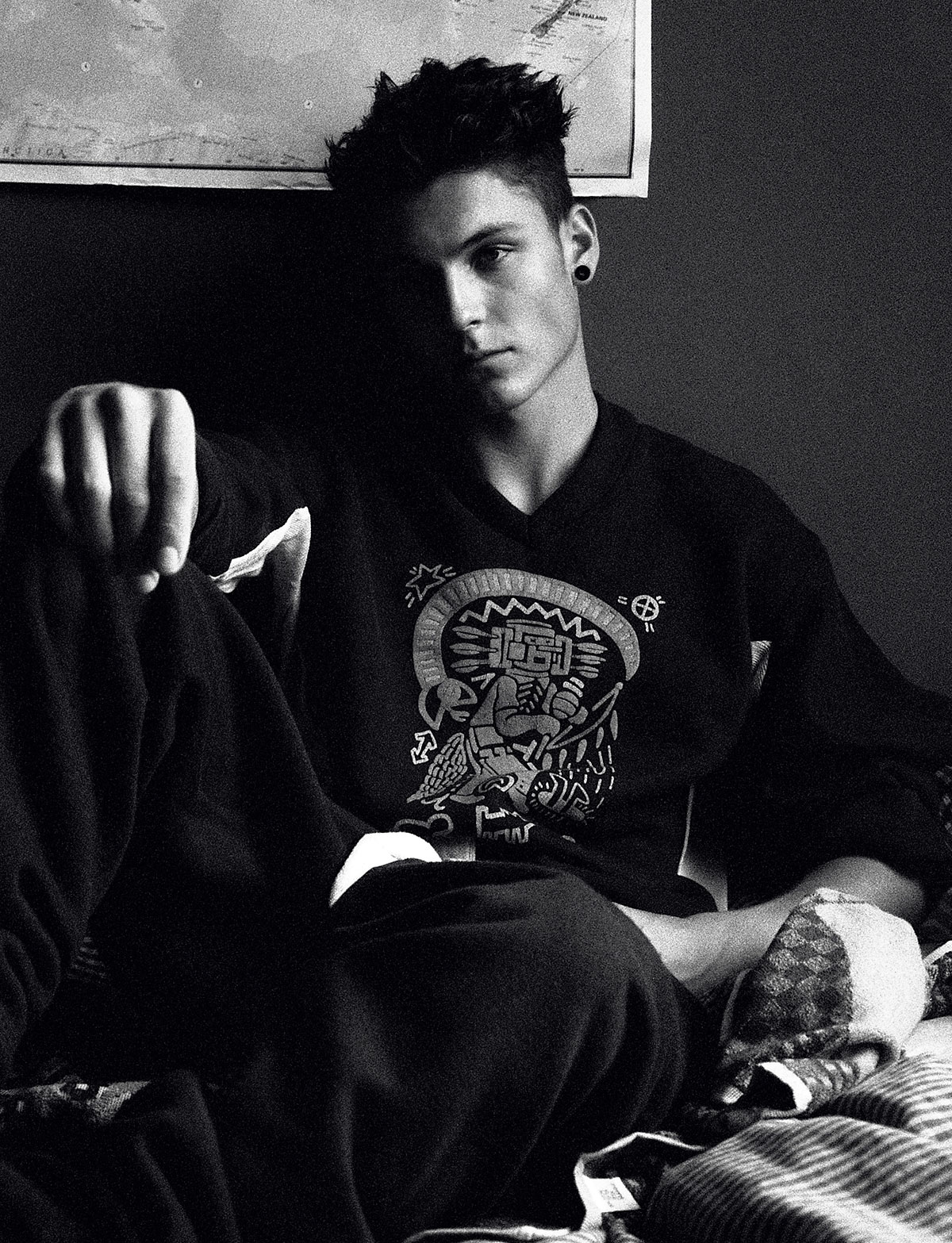

PHOTOGRAPHY FABIEN KRUSZELNICKI

FASHION CHRISTOPHER PRESTON

HERO 12, WINTER/SPRING 2014/15