The acclaimed costume designer of Caravaggio, Orlando, The Wolf of Wall Street and The Favourite has given over 50 movies their style – and won Oscars for her work on Shakespeare in Love, The Aviator, and The Young Victoria. Now she is having her own moment in front of the camera

Sandy Powell is beloved. By her most regular collaborators – the directors Martin Scorsese, Neil Jordan, Todd Haynes – and overarchingly by The Establishment. During this awards season, Powell made history by becoming the only costume designer to have ever been awarded the BAFTA Fellowship. What does that mean? That her lifetime’s creative output stirringly ought to be recognised. Cue the iconic metal totem, in the form of a mask designed by sculptor Mitzi Cunliffe in 1955 – a physical excuse for the cinematic realm to celebrate Powell front and centre of a crowded, talented room in her hometown of London. She has other BAFTAs, of course: for her work on Velvet Goldmine, The Young Victoria (awarded both sides of the Atlantic) and The Favourite.

Powell is now unquestionably the world’s most visible costume designer, and not just because of her shock of brightly coloured hair and signature style. She tells of her most vivid memory, hearing David Bowie’s Starman on the radio for the first time as a 12-year old. Spellbound, it would kick start her upbringing in the avant-garde. Through absorbing everything Bowie-related, Powell learned of the dancer, choreographer and mime artist Lindsay Kemp, a figure she later began working with. “Bowie led onto Kemp, which led onto Derek Jarman,” Powell explains. It is not a bad trajectory.

The first film Powell gave its attire was Jarman’s Caravaggio, also Tilda Swinton’s feature debut, released in 1986. Powell describes the heroic filmmaker, artist and LGBTQ+ activist as generous, and this can be felt through how close he kept those around him: Powell also dressed The Last Of England, Edward II, and Wittgenstein; and Jarman worked consistently with Swinton until his death in 1994.

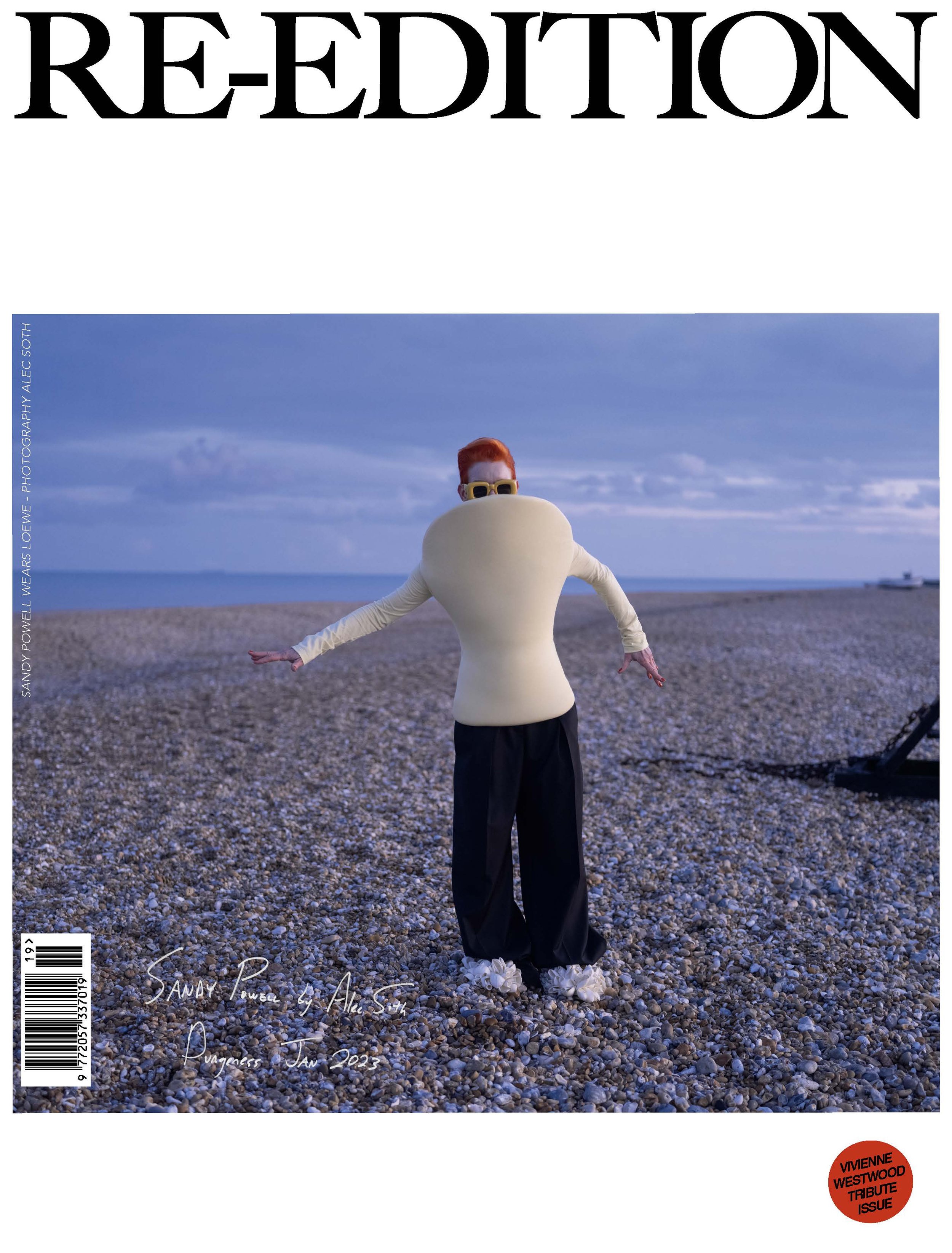

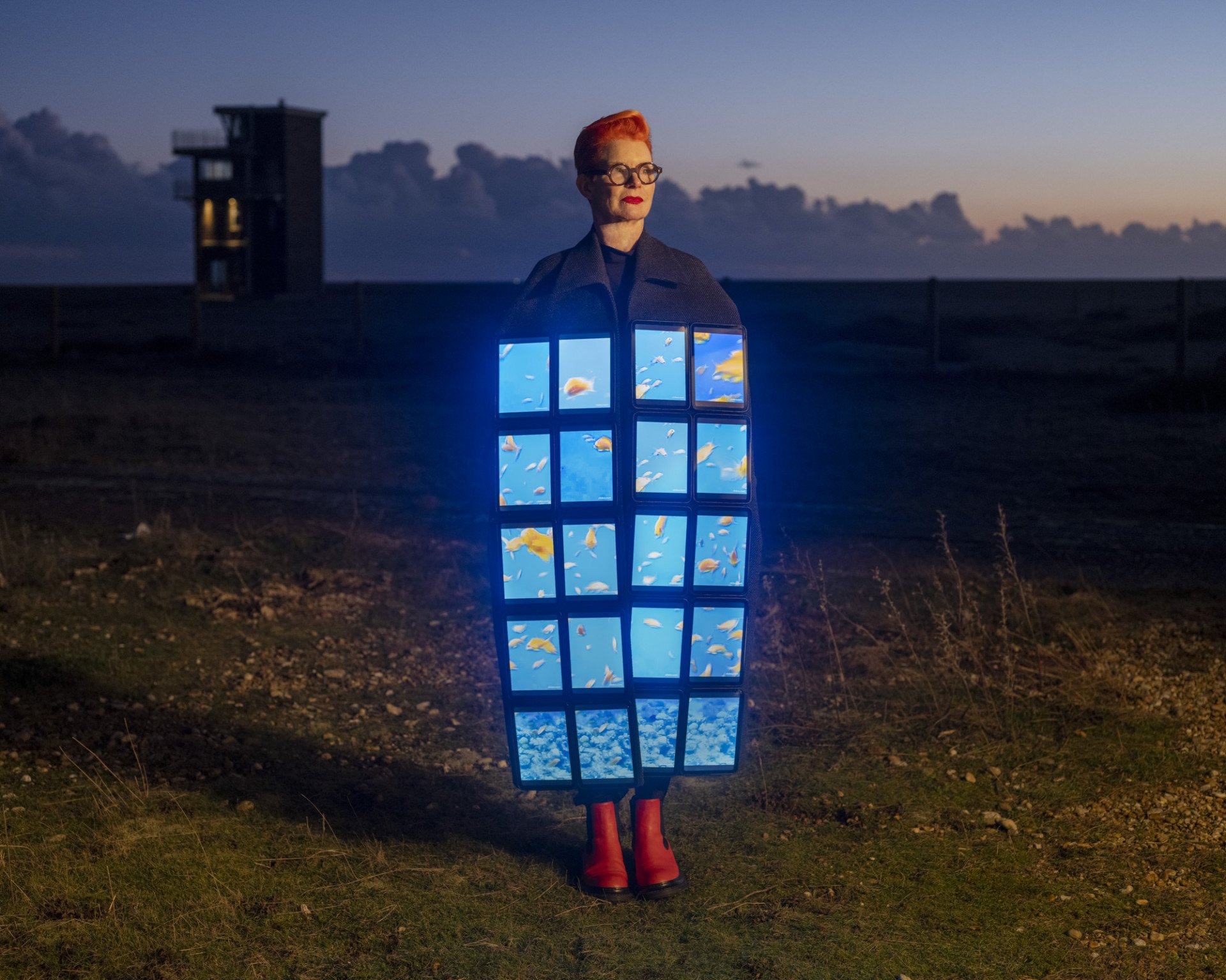

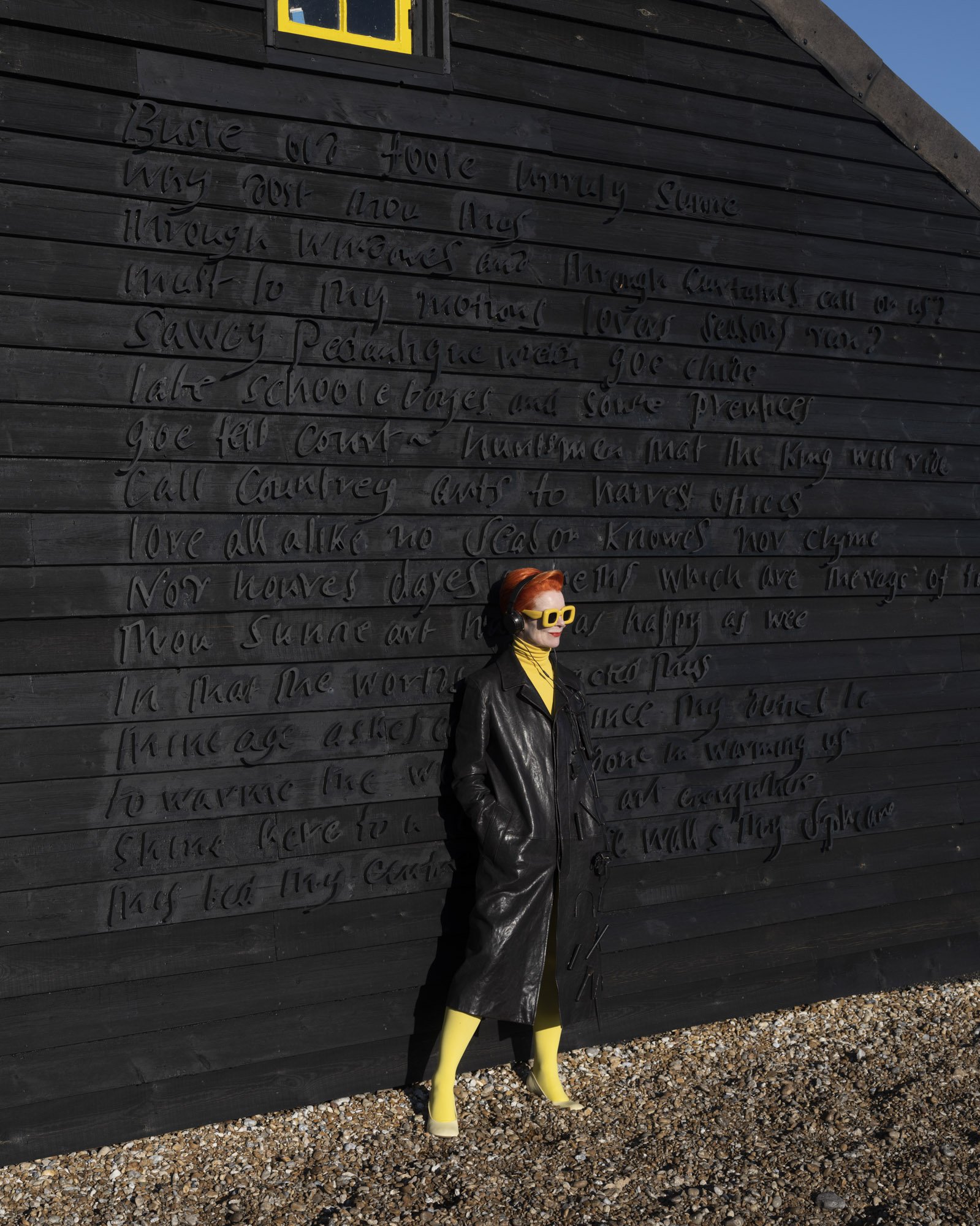

Powell is seen photographed here at Dungeness, in the surrounding energy of Prospect Cottage, the holistic site of Derek Jarman’s life’s work.

In 2020 she wore a calico suit – killer personal tailoring in toile – during awards month, collecting signatures across ceremonies until it was decorated in Sharpie: from Leonardo DiCaprio (who she designed for in Gangs of New York, The Aviator, Shutter Island, and The Wolf of Wall Street) to Laura Dern. Phillips then auctioned it, the proceeds going to maintaining Prospect Cottage and toward its future as an artists’ retreat and residency.

Following Anthony Hopkins in an inspired moment of casting, Powell became a face of Loewe last year, photographed by Juergen Teller. That is the sunny side of what you don’t see: the tireless dedication. Working on The Irishman alongside Christopher Peterson, a film spanning five decades, the pair oversaw 102 costume changes for Robert De Niro alone, and dressed over 6,500 background actors.

You are first costume designer ever to have been awarded the BAFTA Fellowship. What does that mean to you? Are you excited about using it to lift a new generation of design talent?

I’ve been asked what am I going to use it for... I guess it gives me a platform, a position. I’m now technically one of the elders [laughs] because ostensibly, it’s a lifetime achievement award. It’s a fantastic honour, and much nicer for a whole body of work to be recognised than be vying to win in competition with four other films. The most flattering thing about it is that I’m not only the first costume designer but really the first designer, there have been very few technicians who have received this honour: two cinematographers, two editors, one composer in 52 years. Hopefully I can help promote the people behind the scenes as you quite rightly said. I have got where I am today through the generosity of others – my mentors in the past and the people who have given me their time and taken me under their wing.

When you attended the 32nd European Film Awards, you had a charcoal black manicure “to cover the permanent dirt under my fingernails from handling old clothes in costume houses.” I thought that was such a great image.

I would’ve been in the middle of a job and this is the thing: you get filthy. It’s a myth that this job is glamorous. I mean it’s the same with fashion really, behind the scenes is not glamorous.

Christopher Peterson, who earlier in his career worked with you as an assistant, and who you worked together with on The Irishman, described you as being a mix of punk and instinctual. Is he right?

A very nice thing to say. I would describe how I work as instinctual – I can’t ever explain why I’ve made decisions and when people want to know the process or the meaning behind something I’ve done, I always feel a bit intimidated by that question. I don’t have an academic reason for doing something, usually it’s because it felt right [to me]; the colour felt right, the shape felt right. I suppose punk is always referred to as people being a bit risky and not conforming. Obviously I conform to a certain extent because I get my job done and I’ve done lots of mainstream films. But I will always strive to be a bit more interesting, a bit more outside of the box, for want of a better cliché.

Are you still based in the UK? Where do you spend your time?

I live in South London. People always assume I live in America – I have never lived in America, I only stay for the duration of a job if we’re filming there. I’m a born-and-bred Londoner and my family are too. It must influence me. I’m lucky: I’m surrounded by everything that people leave their home towns to come and see and experience.

It’s a city of visual clash, and contrast – in architecture, people mixing together from all backgrounds and ethnicities, traditional style and the punk.

That’s what I like, that it is full of individuals and people who want to be individual. I enjoy being somewhere else because it feels different from here, but I’m always happy to get back.

You’re known for long-running collaborations with a number of directors: Martin Scorsese. Neil Jordan. Todd Haynes. What makes a successful collaboration?

I think it’s like any relationship in your life, not even a working relationship. There’s a mutual respect and understanding. On one hand although communication is very important, you don’t have to ask every single little thing, there is a trust.

You’ve worked seven times with Scorsese. That is really impressive.

Everybody knows he’s got the most incredible mind and knowledge, I don’t know how one person can maintain so much in their memory, he has an encyclopaedic brain. Not only does he have a true passion for what he does, he re- ally loves other people’s work and enjoys celebrating that.

He’s very present in terms of attaching his name – producing.

Exactly. Joanna Hogg, for instance. On the one hand you’d look at her work and you wouldn’t particularly see the relationship between it and Goodfellas, you know [laughs]. But there Marty is. And he’s got a fantastic sense of humour: he’s very, very funny.

Your job has parallels with being a couturier, which is interesting.

To an extent, a lot of what we do is couture, especially when something’s being built from scratch. Sometimes that costume on that person has to go through lots of different changes or has to be running through somewhere; it might be underwater, it might be on fire, it has to do lots of things, which means it requires so many fittings. People are really shocked when they find out how much something has actually cost to make, like a £20,000 dress. Well, that’s because it’s taken many hours, including seven or eight fittings.

In Velvet Goldmine, you ended up recycling a lot of old costumes. Toni Collette wore a negligee and robe that you originally designed for Tilda Swinton.

Oh yes! For Wittgenstein.

Does the idea thrill you of two different actors wearing the same thing for different roles?

I love it. I’m trying to think now of how I’ve done it with other items of clothing... But thanks for reminding me, because I do get a kick out of recycling. I think it’s quite fun for a costume to have a life and be a different thing in a different story. It means something.

There’s something poetic about that. How was working on The Favourite with Yorgos Lanthimos? Because he’s one of the most original and idiosyncratic directors of the last decade. Did those extreme camera angles require you to think in a different way?

Strangely, all I knew was that Robbie Ryan, the cinematographer, was going to be using natural light or candlelight. I had no idea about the angles and when we were actually shooting, Yorgos was in the room with the actors and the cinematographer and the first assistant, and that was it – everybody else was outside trying to look at one tiny little monitor. Which you couldn’t see because they were shooting in natural light. In a way, that didn’t necessarily affect what I did.

With some films you’ve been very historically accurate but with others you’ve worked to benefit the story more. Which was The Favourite?

It’s a bit of both because 1708 was a strange, transitional period. The earlier looks were very late 1600s, a bit like William of Orange. A very, very long line with the high... Do you know a film called The Draughtsman’s Contract? A Peter Greenway film. It was set in that period and it’s a very extreme look. I knew there weren’t any costumes out there available to rent and that from day one we’d have to make every single thing, which is quite a challenge on a really low budget. The whole of The Draughtsman’s Contract was in monochrome so I stole that idea in a way, or I was inspired! It looks stunning. Back when I was a student, I went to see an exhibition of the costumes and was really surprised that all the white costumes were made out of calico, and all the black costumes were made out of black cotton and canvas. The cut was completely historically accurate and all the detailing was really gorgeous and meticulous. So I knew that was a possible thing to do.

The Favourite didn’t have the budget to do royalty; court costumes with massive trains and embellishment, embroideries and jewels, we couldn’t even think about it. And even if we had the money, we didn’t have the time. So we pared it back to the basic silhouette.

And got a BAFTA for it.

Thinking about it now, because of the nature of the dialogue, if there were lots of colours it would have been too busy. So paring it down left room for the dialogue and the story.

Do you relish working with ornate things? I’m thinking of your work on Interview with the Vampire.

Interview with the Vampire is slightly different, because that was a really big period film and that was my first studio big-budget film. It was all a bit scary really in terms of managing a department that big and producing that many costumes, and then of course, the added complication of having Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt to deal with, proper stars, comes with its own baggage. Moving through time is actually a costume designer’s dream: I’ve done Orlando, Interview with the Vampire, The Irishman. I love doing period things and it’s lovely doing rich things. But equally I like doing pared down, realistic things.

And now you are a face of Loewe. Like Chloë Sevigny. And, previously, Anthony Hopkins.

Sixty-two and modelling for the first time! I thought, ‘Why not?’ I love fashion and what Jonathan [Anderson] does.

I re-watched Caravaggio last Sunday afternoon. It’s incredible to think it was the first big job of your career, and it was so early on in the careers of its cast. How was the experience? And how is it looking back on it?

I remember Caravaggio really intimately and I made a lot of friends. It was Tilda’s first film as well [Tilda Swinton]. I thought, ‘Wow, this is great, I want to do this for the rest of my life.’ And I am doing it for the rest of my life but no film has ever been the same.

Working on a [Derek] Jarman film is different from working on anybody else’s film so I’m really grateful to have had that experience. It felt like we were just having fun, that he was making a film because he wanted to make a film. The only restrictions were financial, but there’d always be a way of overcoming it. That’s the way Derek operated. I think he’s having a real renaissance. Students now are brought up knowing who he is and studying him.

In Caravaggio there’s a scene when Lena opens the package with the really sumptuous gown inside and is overwhelmed by a moment of joy as she dances around the room with it. Can you empathise with that?

That’s funny. Do you know what is really sad? I owned that dress for ages afterwards, and I was sharing warehouse space with somebody for storage and it just disappeared. That dress is somewhere in the world and I have no idea where. It was stunning. I remember we painted all the fabric. Yes, it is a lovely moment, isn’t it?

Do you have a large archive?

Technically I don’t own anything. Once a costume’s been made, it belongs to the people who’ve paid for it. So in the case of Disney, they own everything, it gets taken away and archived. Traditionally, smaller firms have tried to get their money back and sold them to costume houses. They buy up whole films and that’s how they increase their stock of period costumes. Pieces get altered, changed, and then by a few years down the line, they’re unrecognisable, they’ve turned into something else. It’s a shame they disappear. I must admit I get possessive about them and would like to know they were all somewhere safe. [But] I don’t need to have them all in my own home, I haven’t got the space.

The autograph suit, which was your way of helping ensure the future of [Derek Jarman’s] Prospect Cottage, is in the collection of the V&A. You couldn’t hope for it to end up somewhere better.

It was auctioned at Phillips but the person who bought it, Edwina Dunn, ended up donating it. I’m very grateful. She’s a businesswoman who runs a charity of her own called The Female Lead. Donating it was such a great thing to do.

How was creating it?

It took a month of events, leading to the BAFTAs and the Oscars. The great thing was that I didn’t have to think about what to wear for the whole month. Normally, if you get those two nominations, you’ve got so many different events and can’t be seen in the same thing twice. So it ends up being bloody expensive. Not having to think about that was what I loved about it.

Did it get easier as more autographs were added?

Yes, it did. And I got less worried about asking people. At the beginning, it was a bit like, ‘What have I done? I might only get three signatures and it’s going to look really silly’ [laughs]. I was at The London Critics’ Circle Film Awards, for which I won kind of a lifetime achievement [the Dilys Powell Award for Excellence in Film]. Wearing the plain suit, I announced in my speech what I was doing. Elle Fanning was there and she was the first person to sign it. Sally Potter was next.

Because of your Derek Jarman years, working with Tilda Swinton on Orlando must have been a great moment.

Orlando was a turning point in my career, because it was a low-budget arthouse film that was then recognised on a larger scale. Myself and the production designers were nominated so we all got to go to the Oscars. It was 30 years ago now.

Sally Potter knew Derek, and a whole lot of the crew, so it sort of felt like a natural continuation. A little bit bigger budget than Derek’s films and probably a more structured film and slightly more conventional in terms of its storytelling.

How did you meet Jarman? Was it through Lindsay Kemp?

No, I already knew Lindsay, who I’d dropped out of art college in 1980 to go and work with. I was aware Lindsay had worked with Derek... I was working in London with experimental, visual fringe theatre companies, and there were many of them who all had Arts Council funding. They’d perform at lots of venues around town but quite often at the ICA. So I spent the early ‘80s at the ICA designing sets, and costumes. I invited Derek to come and see Rococo, one of the shows that I’d worked on with Rational Theatre. I thought, ‘I’ve seen his films and I love them’ and I kind of knew that I wasn’t interested in doing set design in the theatre, I was just interested in the costumes. I procured Derek’s phone number from a friend who’d met him in [gay nightclub] Heaven and invited him to come and see the show [laughs]. Then he invited me round to his flat in Phoenix House on Charing Cross Road for tea. And that was the start of the rest of it – of everything else and the beginning of my career in film.

What are your favourite films? I heard you like The Women.

Oh, I love The Women. It’s just fantastic: those women, the dialogue, the outfits and the fashion show in the middle. Adrian designed it. Strangely, my favourite is Don’t Look Now, the Nicolas Roeg film. It makes me feel something every time I see it: the hairs on the back of my neck stand up. But I think it’s gorgeous. The ones that have stayed with me are the ones that I saw in the ‘70s. I watched Death In Venice seven times as a teenager.

Your create drawings after the costumes have been made. Which can sometimes be up to a year afterwards. Is it like saying goodbye to a character?

I guess it is a way of saying goodbye and it’s also nice to revisit as well. It makes me actually really look at everything. You’re reminding me – there’s a film I finished last July and I haven’t done them yet! I should be doing them now and that’s the other thing, I put off doing it. I think, ‘I’ll do that when I’ve tidied the room, or when I’ve done this other really important job.’

How do you unwind?

I don’t make things out of matchsticks [laughs]. I’m always doing something. One of the things I missed in lockdown was airports, believe it or not. I get quite excited going to an airport.

SANDY POWELL

TEXT DEAN MAYO DAVIES

PHOTOGRAPHY ALEC SOTH

FASHION JO BARKER

RE-EDITION #19, SS23

COVER STORY