Hedi’s Celine was a dressed up riposte to streetwear’s stranglehold. Dean Mayo Davies responds to the designer’s debut at the French fashion house

Paris’s Place Vauban might be famous for the golden dome shining over Napoleon’s tomb, but, for Hedi Slimane at least, it’s likely to have a hidden meaning: Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé moved into an apartment at the address in 1961, filling their home with the beginnings of a haul that would mark them as the greatest art, furniture, and objet d’art collectors of the 20th century.

Celine 01, as the posters in the immaculate art book invite decreed, was also Slimane’s first show since the passing of mentor Bergé. And the night divined all the loaded excitement of his 2001 Dior Homme debut thanks to Karl Lagerfeld, Catherine Deneuve, and Lady Gaga in the front row – with the 00s indie contingent of Alex Kapranos, Carl Barat and George Barnett joined by a new wave of French talent: La Femme, who did the soundtrack, Papooz, Jaune, and London-born Lauren Auder, to name just a few of those defining a new era. Yves Saint Laurent famously attended Slimane’s first Dior catwalk, nailing his colours to the mast by skipping his own house’s ready-to-wear by Tom Ford. He even led a standing ovation. Slimane’s career began as a reversal of Mr Saint Laurent’s, working at Rive Gauche Homme in the 90s, before joining the house described by Cocteau as combining God and gold: Dieu and Or.

But enough of the history, though this city really is the place for that. After weeks of defining very particularly his boy / girl archetype on Instagram; stealthily unveiling the ‘16’ bag and posting the introduction campaign on trucks (New York) and in cities worldwide, Slimane inaugurated his new Celine with ceremonial tribute: two Garde Républicaine drummers – an institution established in 1802 – in their historic finery, beating a rhythm before the set unfolded, inspired by the mirrored interior of a wind-up music box. Their presence felt appropriate – after all, this is a designer who marches to the beat of his own drum.

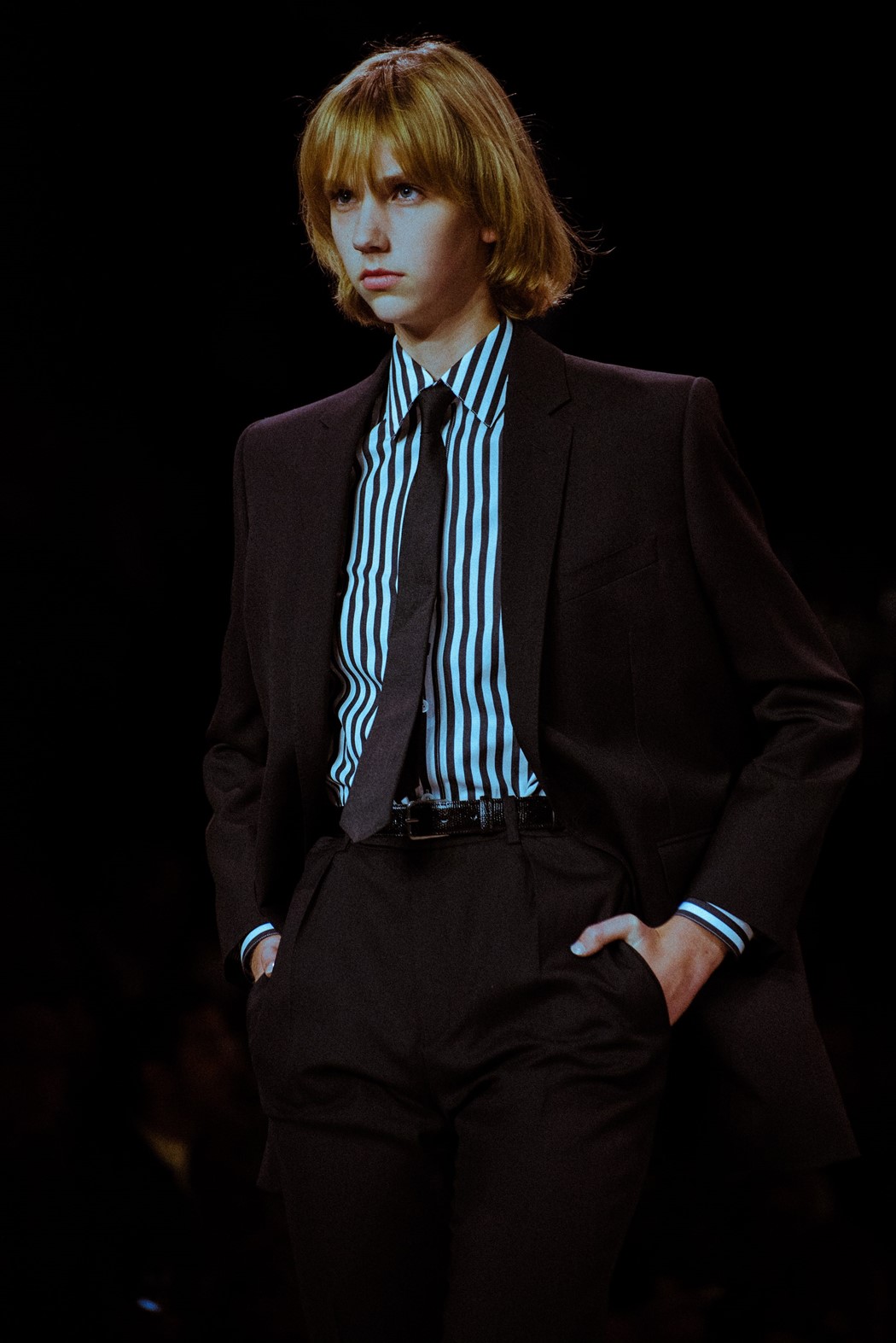

Out came Hannah Motler, in a polka dot silk minidress, with huge, architectural bow and sequinned Parisian ‘Bibi’ hat (‘a tribute to Hedi’s years at Le Palace and Les Bains Douche’). The vibe? It’s Friday night, I’m going OUT, which unfolded over 96 looks of womens and menswear; the tailoring interchangeable, everything coloured by a euphoric feel. There were Novö-style jackets of rectangular volume and shape; slim ties of the ‘Jeunes Gens Modernes’; V-shape derbies; and what Slimane calls ‘Dancing Dresses’: ‘Pouf’ and ‘Mini-Crino’ dresses; dresses embroidered with sequins or draped metal beads. And a dash of Cold Wave spirit. If you don’t know, watch the opening credits of The Hunger, one of the best movie intros ever.

The imagery photographed by Hedi for the invite is the backdrop for this tribute to youth – ‘Journal Nocturne de la Jeunesse Parisienne’. Fourteen hallowed Parisian clubs and night cafés, from Pile ou Face to La Java, via Bus Palladium, Balajo and Chez Castel.

What Slimane has identified in Celine is Parisian air, a way of wearing. It’s like a great perfume in that it’s there and affects everything without being so rational to define, especially to those of us with geographical distance. It’s the grounding for, over time, a compelling and mysterious narrative. The savoir faire of Celine has ultimately been underscored by the couture work Hedi’s brought, creating a specialised atelier.

This noticeable human feel; the hand, and time, historic skill is a riposte to the print ‘em up and sell-em jersey streetwear narrative. Sophisticated fashion takes preternatural focus, even when you can’t see it. There is devotion to the extreme in realising truly special things.

Celine, in recent years, has become a byword for a figurative art world uniform. Hedi offered a sensational Christian Marclay collaboration, on bags, parkas – yes you can wear those on a Tuesday afternoon – and deep couture embroideries: a kimono and an entirely hand-embellished dress. Which raises a powerful point: why wear a uniform when you can wear the art?

Some people undoubtedly won’t like it – and they will have decided that before the show. Yet, there were acerbic words uttered by a few who really should’ve known better during Slimane’s sympathetic restructuring of Saint Laurent, a project where the couture griffe was given back to Yves, whilst preserving Made in France tradition with the fine atelier at Angers (yes, the irony of that name, said in an English accent, isn’t lost).

Paris fashion, the metier at its most haute, is of course marked by scandal: 1947 Dior, 70s Saint Laurent, 80s Gaultier, now Slimane. To address a churlish point about Hedi’s Celine not being ‘Phoebe’s Celine’: it wasn’t hers when she started either. She opened a studio in London, bypassed the historic maroquinerie to create her own language and even redesigned the logo, adding an aigu. Imagine that!

Appointing Slimane, another agenda-setting designer, comes with a certain point of view. The idea of deviation; stylistic karaoke and a ‘studio feel’, was not an option. Nor should it be.

“Our respective styles are identifiable and very different,” Slimane commented in an interview with French newspaper Le Figaro this week. “You don't enter a fashion house to imitate the work of your predecessor, much less to take over the essence of their work, their codes and elements of their language. The goal is not to go the opposite way of their work either. It would be a misinterpretation. Respect is to preserve the integrity of everyone, to recognise things that belong to another person with honesty and discernment.”

What is vital now is Hedi’s bold assertion of his own language, his specific and unwavering intellectual property. For more on the impact of that, just look at the loyalty of the crowd, here 20 years on.

THE FIRST RUNWAY SHOW, CELINE BY HEDI SLIMANE

SPRING/SUMMER 2019

PARIS, 28TH SEPTEMBER 2018, LES INVALIDES

TEXT DEAN MAYO DAVIES

PHOTOGRAPHY GIACOMO CABRINI

DAZED DIGITAL, SEPTEMBER 2018